A tangible, two-state quantum system known as a physical qubit is the basic component of a quantum computer. Similar to how a transistor is the physical embodiment of a classical bit, it is the physical realization of a qubit.

Here’s a detailed explanation:

What is a Physical Qubit?

In order to properly define and manage the |0⟩ and |1⟩ states, a physical qubit must be able to encode the qubit’s degree of freedom. Physical qubits can be used in modalities that involve more than two states, although two-level physical systems are the optimum. The real hardware parts that display quantum characteristics are represented by them.

At the same time, a physical qubit can exist in a superposition of both states, unlike a conventional bit, which can only exist in either state. The ability to analyze large amounts of data in parallel and possibly execute some calculations exponentially quicker than traditional computers is made possible by this trait as well as entanglement, which occurs when two or more qubits are connected and share the same fate.

However, one physical qubit is fragile and error-prone. Physical qubits can be noisy due to intrinsic properties or environmental interactions, causing modest manipulation errors. In the long term, these variations can compound and compromise a computation’s integrity. For example, a 256-qubit neutral atom quantum computer comprises 256 atoms, which is a 1:1 ratio; in the current early-stage Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) period, the term “qubit” is essentially synonymous with a physical qubit also.

You can also read Space Moths, first quantum-powered MMOG by MOTH & Roblox

History

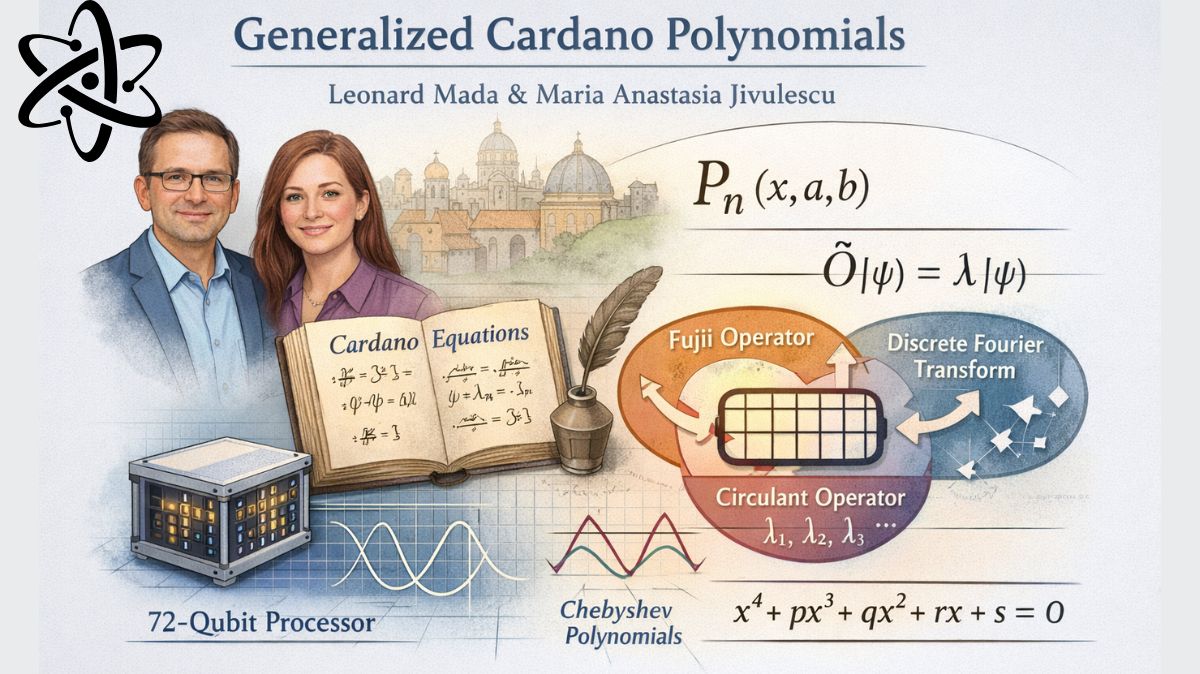

Paul Benioff and Richard Feynman argued in the 1980s that a quantum computer could recreate physical systems more precisely than a classical one. Benjamin Schumacher coined “qubit” in 1995. The field has advanced quickly since the 1998 demonstration of the first quantum algorithm. Traditionally, the emphasis has been on creating meaningful logical qubits by enhancing their quality (fidelity) and creating strong error correction techniques, rather than just increasing the quantity of physical qubits.

How It Works

Information is encoded by a physical qubit using a particular physical characteristic of a quantum system. For instance, the |0⟩ and |1⟩ states can be represented by the energy levels of an atom or the spin of an electron. Path, time-bin, or polarization can be used for encoding photonic qubits.

To execute quantum processes, these states must be carefully manipulated and controlled. Several techniques are used to do this:

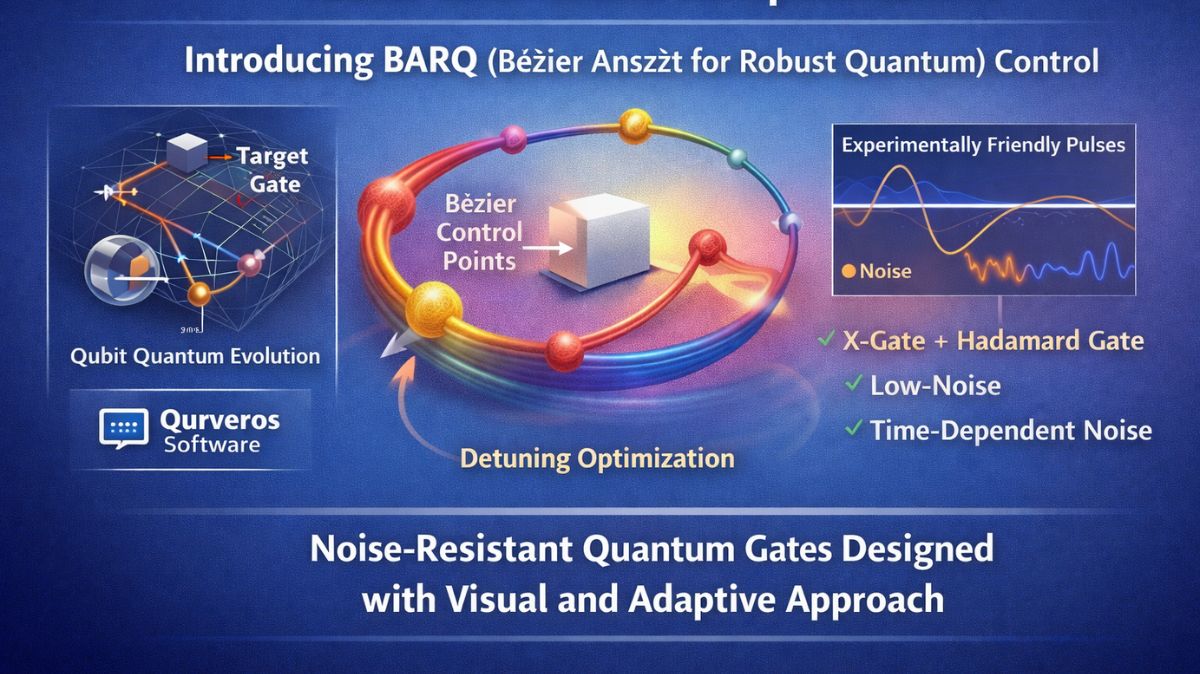

- The manipulation of superconducting qubits is frequently accomplished by microwave pulses.

- Neutral atoms or trapped ions can have their states controlled by laser pulses.

- Electron spin can be influenced by magnetic fields.

- Analogous methods can also be used.

Being able to be in a superposition is what gives a qubit its power. The quantum state of a qubit determines the chance that its state “collapses” to either a 0 or a 1 when a measurement is made on it in superposition. Since physical qubits carry information, they are an essential necessity. They are employed for the representation of input data, computations using quantum gates (including single-qubit and two-qubit gates), and outcomes.

Advantages

Superposition and Entanglement: Superposition and entanglement are two characteristics that allow quantum computers to analyze large volumes of data in parallel, which could result in speedups for particular issues.

Exponential Scaling: A system’s computing space doubles when a single qubit is added, enabling the representation of a vast number of states with comparatively few qubits. This phenomenon is known as exponential scaling.

Specialized Problem Solving: Physical qubits are particularly well-suited to difficult optimization and factorization issues as well as the simulation of quantum systems, such as molecules.

Disadvantages

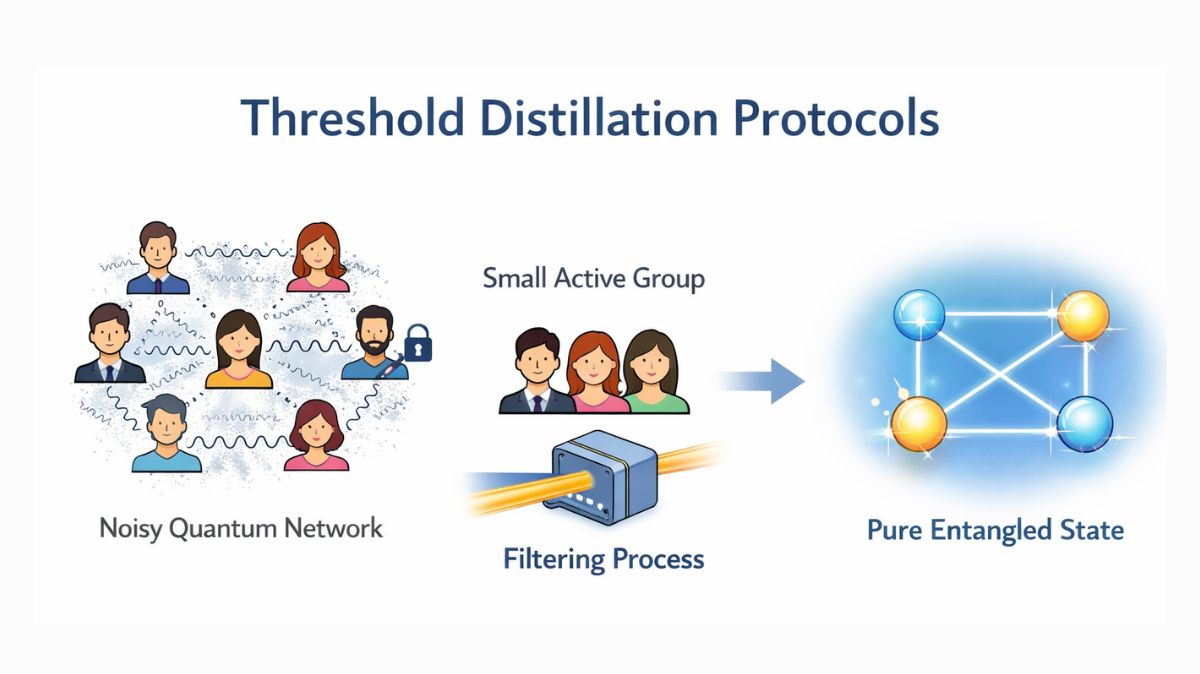

Decoherence: Because of their sensitivity to external noise, such as temperature changes or electromagnetic radiation, qubits may introduce mistakes and lose their quantum state. Calculation times are constrained by this loss of quantum information.

Scalability Challenges: It is challenging to increase a system’s qubit count. As the number of qubits increases, controlling each one individually and reducing interference (crosstalk) becomes a significant engineering challenge.

High Error Rates: Due to the natural tendency of physical qubits to make mistakes, sophisticated and resource-intensive quantum error correction methods are required. Thus, to produce a single, stable logical qubit, several physical qubits are required.

Types and Implementations

Every physical qubit implementation has advantages and disadvantages, hence there is no one “best” way to implement them. This promotes continuous research into new modalities. Physical systems are used to categorize major architectures:

- Superconducting Qubits: Using superconducting circuits that run close to absolute zero, superconducting qubits are created. They are sensitive to noise and need extremely cold conditions, yet they are quick and can be made with current chip-making technologies. Companies that use them include Google and IBM.

- Trapped Ion Qubits: Using charged atoms (ions) suspended and controlled by lasers and electromagnetic fields, trapped ion qubits are employed. They are often slower than superconducting qubits and challenging to scale, but they provide high-fidelity operations and lengthy coherence durations.

- Neutral Atom Qubits (or Cold Atoms): Use qubits of neutral atoms, often known as cold atoms, which are maintained in position by lattices or optical tweezers. Their scalability is promising due to their extended coherence durations and ability to be organized in huge, reconfigurable arrays. Since they are not produced, atoms are regarded as identical and flawless, negating the need for additional calibrations or the mapping of circuit qubits to physical qubits to reduce error rates or improve connections. Aquila is the biggest quantum computer that is openly accessible and uses 256 neutral atoms.

- Photonic Qubits: Encode data using individual photons, which are light particles. They are difficult to use for intricate computations but are great for quantum communication and run at room temperature. There are various techniques for encoding photons:

- Two orthogonal light vibration directions, such as horizontal and vertical, are used in polarization encoding.

- The “dual-rail” or path encoding method makes use of a photon in one of two fiber optics.

- A photon’s timing inside a predetermined period (early or late) is used in time-bin encoding.

- Electron Spins: Individual electrons’ intrinsic spins can be used to encode information; these electrons may be confined in carbon lattice vacancies, quantum dots, or vacuum chambers.

- Quantum Dots: Quantum dots are electron-constricting semiconductor nanocrystals in which electron presence superpositions convey information.

- Nitrogen Vacancy (NV Center): Either the electron spins in the vacancies or the nuclear spins of nitrogen atoms include information encoded by the nitrogen vacancy center (NV Center). NV Center’s largest known device has two qubits.

- Topological Qubits: Information is encoded in topological qubits, which are still theoretical and are made by the physical motions of qubits.

Challenges

Many significant obstacles must be overcome in order to construct a workable, large-scale quantum computer from physical qubits:

Coherence: Longer computations require extending the amount of time a qubit may hold its quantum state before decoherence takes place.

Scalability: Scalability is an important engineering and manufacturing challenge that involves increasing the number of qubits while preserving excellent performance and low error rates.

Error Correction: Achieving a “fault-tolerant” quantum computer requires the development of effective and workable quantum error correction codes (QECC) that can be placed into hardware. The use of physical qubits can be unfeasible without error correction due to their intrinsic noise.

Crosstalk: As systems become larger, it becomes increasingly important to reduce undesired interactions between nearby qubits.

Applications

Numerous possible applications are based on physical qubits, including:

Quantum Simulation: Complex molecules and materials can be simulated using quantum simulation, which may result in advances in material science and medication development.

Optimization: Resolving intricate optimization issues in a variety of domains, such as supply chain management, finance, and logistics.

Cryptography: The use of algorithms such as Shor’s algorithm to break current encryption techniques while simultaneously making it possible to create new, more secure quantum-safe encryption.

Artificial Intelligence: Enhancing machine learning and AI algorithms through more effective processing of large datasets is known as artificial intelligence.

You can also read What Is QMM In Quantum Developed By Terra Quantum

Thank you for your Interest in Quantum Computer. Please Reply