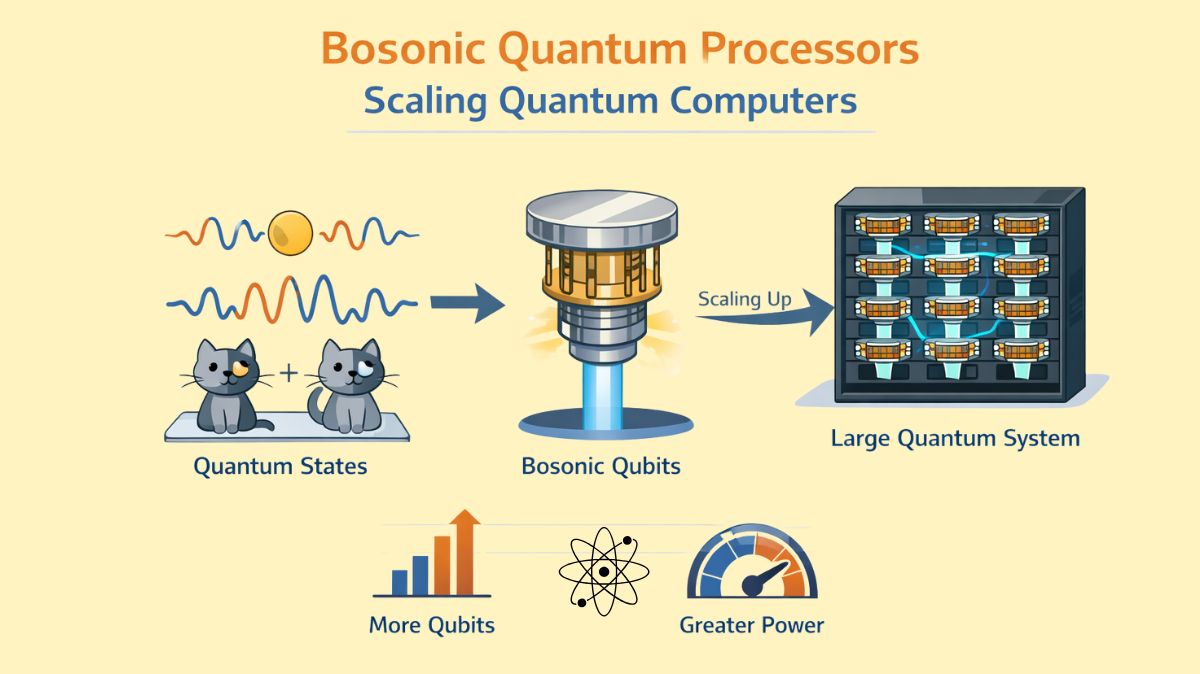

A key idea in quantum physics are quantum states, which are the mathematical representation of all the information about a quantum system. They talk about “the way quantum things are right now and how they might change” . In contrast to classical states, which are made up of dynamical variables with deterministic evolution and well-defined real values, quantum states produce values that are complex, quantised, and constrained by uncertainty. They also only give a probability distribution for the measurement’s results.

What are quantum states?

At its core, a quantum state is an abstract mathematical idea. It is a part of the Hilbert space, a mathematical space. Abstract vector states are frequently used in modern professional physics, even though wave functions (Ψ(x, t)) have traditionally and in many introductory contexts been used to define quantum states. The likelihood that a measurement of a particle’s position would provide a result within a specified interval is represented by the square of the wave function’s absolute value, |Ψ(x, t)|² dx. The entire probability of discovering the particle must be unity, which means that the wave function must be normalisable.

One cannot just “observe” a quantum state directly; rather, it is a reality created via theoretical ideas. To modify, edit, record, and analyse signals from the interfaces where quantum phenomena take place, experimenters are required in place of “observers” in the traditional sense. The foundation of the quantum-physical theory of reality is the idea of a quantum state.

Also Read About Quantum State Tomography Cuts Three Qubit Measuring Needs

How Quantum States works?

Several fundamental ideas that set quantum states apart from classical descriptions regulate their nature and behaviour:

Mathematical Representations

- In a complex Hilbert space, vectors of norm 1 denote pure states. On its own, multiplying a pure state by a non-zero complex scalar has no physical effect.

- A density matrix (ρ), a Hermitian, positive semi-definite operator with a trace of 1, can characterise both pure and mixed states. In a mixed state, Tr(ρ²) < 1, but in a pure state, ρ = |ψ⟩⟨ψ|.

- A linear combination of orthonormal basis elements, which are frequently the eigenstates of a measurable observable, can be used to express any state.

Pure vs. Mixed States

Deterministic probability amplitudes define a pure state. A single ket vector, like |ψ⟩, can describe it. Pure states include eigenstates, which are Schrödinger equation solutions that provide a well-defined value of an observable without quantum uncertainty. An electron’s spin can be represented as a one-length two-dimensional complex vector (α, β). Experimental outcomes are usually compared to statistical mixtures of solutions since experiments rarely create pristine states.

Mixed states are probabilistic mixtures of pure states. These occur when the system’s preparation is unknown or when describing a physical system entangled with an inaccessible one.

The Superposition Principle

- Linearly merging quantum states creates new acceptable states, a fundamental quantum mechanics premise. If |α⟩ and |β⟩ are quantum states, then |cα|α⟩ + cβ|β⟩ is also possible, where cα and cβ are complex numbers.

- This means a quantum system can live in numerous states until measured. This principle causes quantum interference, as shown in the double-slit experiment.

Entanglement

Quantum systems with several subsystems exhibit entanglement, a unique characteristic. Entangled systems have quantum states that cannot be separated.

In entangled states, particle measurements show statistical connections that classical theory cannot explain. These correlations are needed for quantum computing and information processing. The Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) thought experiment emphasises quantum states’ potential rather than objects’ attributes by highlighting real-space entangled states and correlations. Probing one component of an entangled system immediately suggests a state for the other, but superluminal signalling is not needed because the entangled state already has these correlations.

Measurement and Uncertainty

- The measuring process in quantum mechanics differs from classical mechanics, as it alters the system’s state. A measurement leaves the system in an eigenstate matching to the measured value.

The Heisenberg uncertainty principle limits the precision of simultaneous knowledge of physical properties like location and momentum. If one is known precisely, the other is lost. This is a physical constraint, not a measurement flaw. - Due to the probabilistic nature of quantum results, a single measurement produces a random value from the state’s possibilities. Multiple observations on identical quantum states are needed to obtain a probability distribution.

- The traditional idea of a “observer” collapsing the wave function is questioned. The quantum state dictates the outcome, and interference patterns can arise or disappear without an observer.

Time evolution

- Deterministic evolution of an unperturbed quantum system is regulated by the Schrödinger equation. Time-dependent coefficients of a superposition of eigenstates demonstrate quantum state transitions.

- Both the Heisenberg and Schrödinger pictures can describe time evolution: observables depend on time and the state is fixed, or observables are fixed and the state depends on time.

Material Linkup and Reality

A quantum state is maintained by a material system. The exact localisability of the material system is not always a problem for the quantum state itself, but it must be present in the area where quantum transitions take place. Hilbert space is home to the abstract idea of the quantum state itself.

Applications and Experimental Insights of Quantum States

Numerous investigations have shown that the special qualities of quantum states are not only theoretical constructions but can have significant ramifications for a range of applications:

Quantum Computing and Information

Quantum computing uses the collective characteristics of quantum states, including entanglement, interference, and superposition, to carry out calculations.

One essential method for empirically reconstructing unknown quantum states is quantum state estimation, sometimes referred to as quantum state tomography. To do this, several identically prepared systems must undergo a series of suitable measurements. Among the techniques are Bayesian mean estimation, linear regression estimation (LRE), and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). The fact that the reconstruction’s dimension and parameter count grow exponentially with the system size (number of qubits) presents a major obstacle.

The special characteristics of quantum states are also essential to quantum information protocols like quantum teleportation and quantum cryptography, commonly referred to as quantum key distribution. The basic components of quantum information processing are qubits, which are two-level quantum mechanical systems.

Experimental Demonstrations

Double-Slit Experiment

This well-known experiment validates wave-particle duality by showing that individual particles, like electrons, may “behave like a wave” and create interference patterns. The existence of two slits affects the behaviour of individual electrons.

Scully et al. Atom Interferometer Experiments

The Atom Interferometer Experiments by Scully et al. show how the results are determined by the physical quantum states that impinge on a screen. The interference pattern may diminish if interaction with cavities causes the beams to emerge in distinct quantum states. Importantly, the quantum state itself is sufficient for the formation or disappearance of interference patterns; no “observer” in the sense of collapsing the wave function is needed.

Also Read About Groove Quantum Gets €10M from EIC To Advance Germanium

Quantum Eraser

This setup investigates the connection between interference and “which-way” information. Although interference fringes may vanish as a result of “which-path” information, this is because the entire quantum state is a combination of alternatives rather than because of correlations between the measuring device and the observed system. Interference patterns (also known as anti-fringes) can be recovered by “distilling” or sorting the data according to detector results, showing that the information was always there but confused. It is clearly stated that “correlations between event on the screen and the rubber photocount are necessary to retrieve the interference pattern” are not required.

Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) Paradox

Real-space entangled states and their statistical correlations that defy conventional explanation are highlighted in this thought experiment. The fundamental distinction from classical perspectives is that quantum states describe possibilities as opposed to object attributes. Quantum correlation is demonstrated without superluminal signalling when one component of an entangled system is probed, as this immediately indicates a state for the other.

Wheeler’s Delayed-Choice Experiments

These experiments show that the quantum state being probed at the detectors, rather than how it is observed classically, determines the result. The popular claim that “quantum entities can behave like particles or waves depending on how they are observed” which is informed by classical physics is called into question by this. Quantum states behave in Hilbert space as such; they can be manipulated and diffracted to produce interference patterns, but they exchange energy in quanta upon detection.

Also Read About Quantum Computing Hefei Became China’s Innovation Model

Quantum Boundary Gravitational State

There is experimental proof that neutrons can exist in gravitational quantum bound states. The neutrons in these experiments hop between discrete heights instead of moving continuously because they are falling towards a horizontal mirror and Earth’s gravity creates a restricting potential well.

Macroscopic Quantum States

Charge-density waves (or CDWs) can manifest as macroscopic quantum states or quantum condensates in one-dimensional van der Waals materials. The electronic spectrum opens up an energy gap as a result of these quantum states. Collective quantum states can be seen even in atomic chain bundles as small as 100 nm.

Thank you for your Interest in Quantum Computer. Please Reply